Image: Breguet, luxury watchmaker

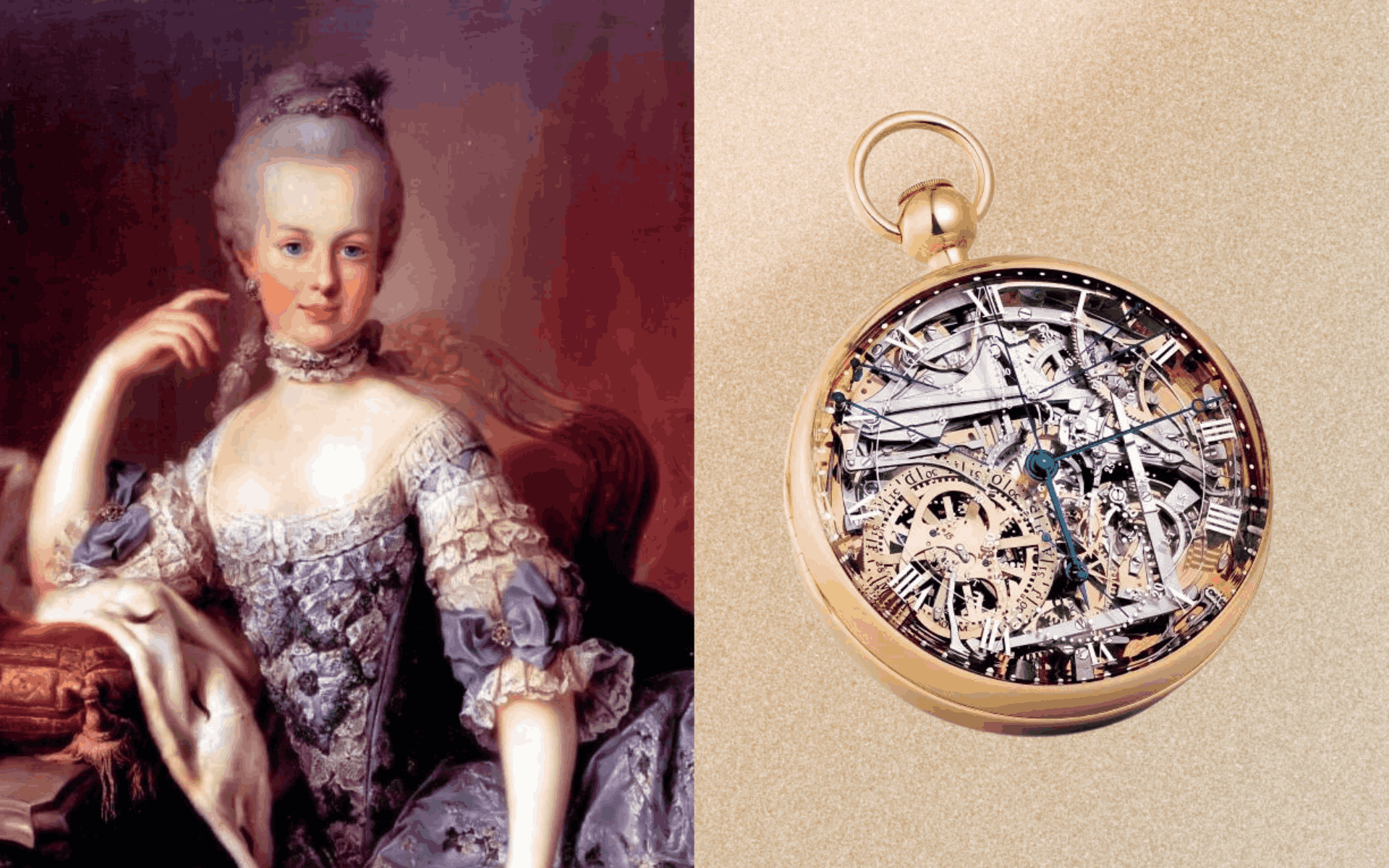

In 18th and 19th-century European royalty, time was not only measured but also captured in instruments, both on the wrists and in palaces of monarchs. Beyond their practical function, watches became symbols of status, prestige, and even personal connections. One such connection was forged between the last reigning Queen of France and Breguet. Marie-Antoinette was known for her fascination with Breguet’s watches, gradually amassing a collection of his timekeeping instruments over the years. In 1783, a mysterious admirer commissioned the watchmaker to create an exclusive piece as a gift for her. This watch was intended to exemplify the pinnacle of clockmaking, incorporating a vast selection of fine mechanisms and utilizing gold as much as possible. The commission stood out for its absence of time or financial limitations, allowing the creation of watch number 160.

Having long been a supplier to the French court, Breguet was given complete freedom with this commission. Unfortunately, the Queen never got to see her gift, which was later named the “Marie-Antoinette” in her honor. The watch was completed in 1827, 34 years after her death in 1793 and four years after Breguet’s, marking 44 years since the initial order was placed.

The completion of the watch was a significant moment in the history of horology. It showcased the best of 18th-century skills and served as a reminder of a past era. As one of Breguet’s finest works, it was both beautiful and technically advanced, attracting people from far and wide. The long delay in finishing the watch added to its charm and mystery, turning it into a token of diligence and finesse that endured through the years.

In the 1920s, the “Marie-Antoinette” found its way into the collection of Sir David Salomons, a distinguished Breguet enthusiast. Driven by a passion for preserving chronometric treasures, Salomons generously donated his entire Breguet collection to the L.A. Mayer Institute for Islamic Art in Jerusalem, ensuring that these would be admired and studied by future generations.

However, on the night of April 15, 1983, the tranquility of the museum was shattered. Under the cover of darkness, a group of thieves scaled the museum wall using a rope ladder, slipped through a narrow 20-inch window and exploited the malfunctioning alarm system. In a swift and silent operation, they vanished with over 100 timepieces and music boxes, including watch number 160, with an estimated worth of INR 25.17 crore ($30 million). The guards, oblivious to the audacious theft, remained completely unaware of the monumental loss that night. That is until 2006, when the museum alerted Israeli authorities that someone had attempted to sell the stolen items, including the Breguet. This led to the recovery of the watch, which was then returned to the museum in 2007.

The return of the watch was a moment of victory and relief for the museum, which had long mourned its loss. The recovery not only restored a part of their collection but also reignited interest and appreciation for Breguet’s work among historians and admirers. It highlighted the influence of Marie-Antoinette and her connection to Breguet’s classic designs.

In 2004, Nicholas G. Hayek, CEO of Swatch Group, challenged Breguet’s watchmakers to build an exact replica of the then-stolen pocket watch. Recreating the numerous complications using only historical documents presented a challenge for the firm’s technicians and watchmakers. The original technical drawing from the Breguet Museum archives and cultural sources from the Musée des Arts et Métiers in Paris were the sole sources of information and guidance for the watch’s functions and design details. By comparing the planned watch with contemporary pieces, they uncovered novel design elements and workshop techniques from that century, revealing partially forgotten skills that enabled Breguet to create a watch that faithfully replicated its legendary predecessor.

This led to the birth of the new Marie-Antoinette perpétuelle (self-winding) watch, a story of brilliance, featuring numerous sophisticated elements. It includes a minute repeater that chimes hours, quarters and minutes on demand, as well as a comprehensive perpetual calendar displaying the date, day and month at two, six and eight o’clock. At ten o’clock, an equation-of-time display indicates the subtle difference between civil and solar time. Central to the design are jumping hours and a minute hand, complemented by a large independent seconds hand—a precursor to the chronograph hand—with a subdial for running seconds at six o’clock. The watch also has a 48-hour power reserve indicator and a bimetallic thermometer positioned side by side.

The heart of this watch, its self-winding movements known as perpétuelle in Breguet’s time, is composed of 823 finely crafted parts and components. Plates, bridges, bars and all moving parts of the motion-work, calendar and repeater mechanisms are fashioned from wood-polished pink gold, while the screws are made from blued and polished steel. Sapphires are fitted at all friction points, sinks and bearings, highlighting the attention to detail. The fine design also includes a special escapement with a natural lift, a cylindrical balance spring in gold and a bimetallic balance. To protect its delicate mechanics, a double parachute shock-protection device is in place to shield the balance-wheel staff and the oscillating weight arbors from impacts and jolts.

In April 2008, after four years of research and painstaking reconstruction, the new Marie-Antoinette N°1160 was finally revealed. Around the same time, an oak tree in Versailles under which the Queen herself once rested succumbed to a winter storm. This event deeply moved Hayek, inspiring him to acquire the fallen tree and use its wood to make a presentation case for the watch. Through this gesture, the watch assumed the role of a tribute to both the past and the present, honouring the relationship between the French Queen and Breguet.

Discover more stories on luxury, business, culture, and innovation here at Candle Magazine